Restorative practices & relationship-based education

Download this article as a PDF ![]()

There tend to be two understandings of a “restorative approach” and/or “restorative programs” in schools: one is simple, perhaps simplistic, the other is more complex.

The simpler version

The simpler version of restorative practices in schools arose from programs developed since the mid-1990s in Australia and New Zealand, and then North America, Europe, and beyond. It has involved:

- Running the occasional community conference to address some specific harmful incident;

- In some schools, implementing ‘circle time‘ – regular structured discussion in a circle format to build relationships.

Both of these activities can be highly valuable. However, the label of “restorative” conversations has also masked some inept and counterproductive practice. Kristin Reimer of Monash University has identified a foundational reason for the difference between good and bad practice:

“Restorative Justice [RJ] is a window into the character of school relationships since it provides a view of those relationships. RJ is used in the service of predominant relational objectives in the school. A school in which relationships are ones of social control – based on compliance, rules, behaviour, punishment and seeing students as isolated individuals – will utilize RJ to strengthen that control. A school in which relationships are ones of social engagement – based on relationships of equality and mutuality, with a broad focus that encourages the realignment of power – will utilize RJ to strengthen that engagement.”

The problems

In the absence of a coherent and appropriate philosophy, and appropriate skills development, staff can find themselves:

- Not confident to conduct a restorative process

- Speaking for a student

- Demanding an apology

- Insisting they must be correct.

Students can find themselves:

- Disputing claims

- Going through the motions

- Feeling the process is “stupid and dumb”

- Becoming heated & oppositional

- Struggling to empathise.

So there is the problem that a restorative approach, if poorly understood and inexpertly applied, can simply compound problems with existing behaviour management practices. Fortunately, there is now a growing realisation among educators that the more sophisticated or complex approach to “restorative practices” in schools can deliver significant, sustained improvements in student and staff wellbeing.

A broader approach

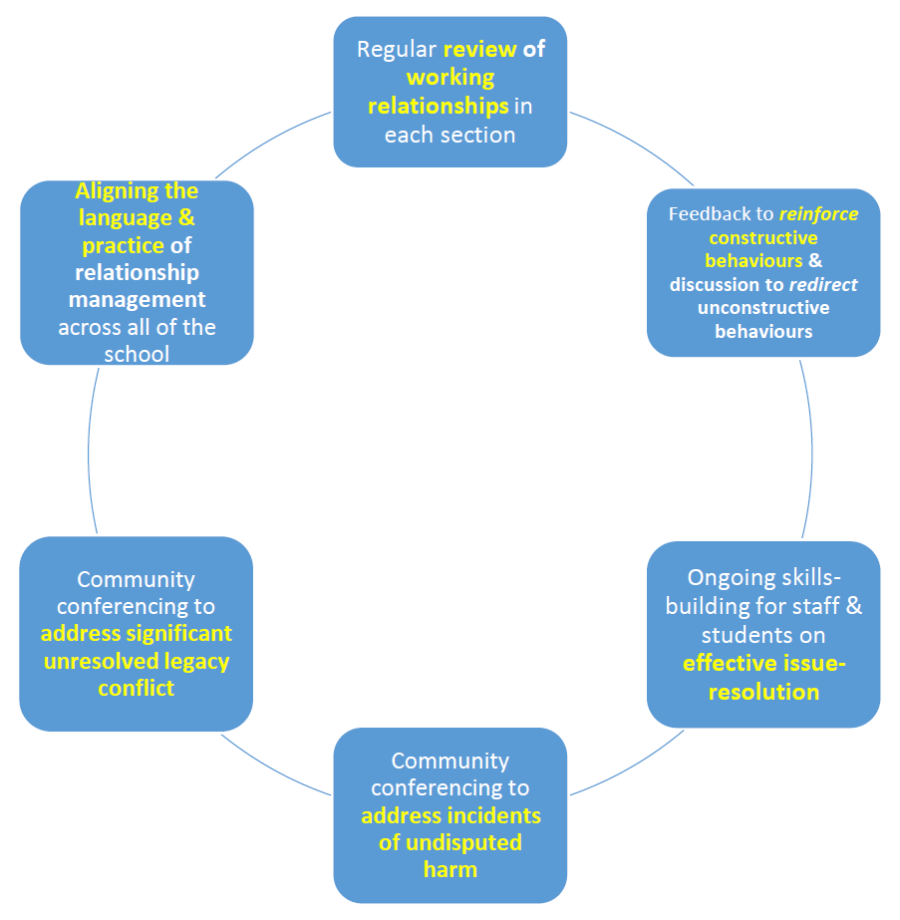

Restorative practices in schools are more usefully understood as part of a broader approach to effective relationship management. This more complex, systemic, school-wide approach can provide positive support for respectful relationships by applying a set of teachable / learnable skills.

Coordination is required to ensure a common understanding or mindset about relationship management, and a common set of practices or skillset (described with a shared language).

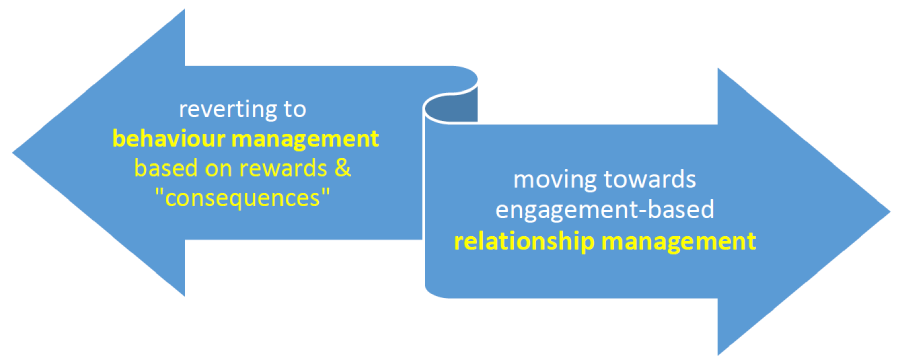

To support the move beyond behaviour management based on “consequences” and rewards, and towards relationship management, requires a virtuous circle of reform – where each element of reform supports other elements. A virtuous circle of mutually reinforcing effective practice in schools will likely involve the following elements:

It is important to understand that restorative practices, as part of comprehensive-relationship-management, are not just another program. Rather, they provide important techniques – the “how to” – for implementing, reviewing, fine-tuning and aligning programs such as:

- School Wide Positive Behaviour Support

- Respectful Relationships

- Protective Schools

- More general social movements such as Positive Education.

The full set of techniques – from effective coaching through facilitating large meetings – can support each element of this virtuous circle in a school community:

| Communication mode | responding ⟷ preventing ⟷ promoting |

| One-way | correcting ⟷ coaching ⟷ mentoring |

| Two-way | Structured conversations |

| Mediated | Third-party assisted negotiations |

| Facilitated | Group meetings in various formats |

Key applications for these facilitated restorative group meetings – with a format for each application – are as follows:

Group meeting applications and formats

| A legacy of past trauma | Undisputed harm in the present | A sequence of unresolved incidents and/or issues | Issue(s) of common concern |

Restorative engagement:

|

Community conference focussed on an incident to enable recognition, reasons, responsibility & regret for harm THEN redress to repair harm, with planning to prevent further harm, & to promote well-being | Community conference with a chronological narrative to enable recognition, reasons, responsibility & regret for harm THEN redress to repair harm with planning to prevent further harm, & to promote well-being | Making sense of complexity through a collective narrative & coordinated action |

Supporting research

The philosophy and techniques of restorative practices have important parallels with what we now know about effective methods of teaching and learning more generally. These evidence-based techniques can support members of a school community to improve the way they establish, maintain and repair relationships.

The results of a randomised control trial of this approach, conducted over three years in state schools in the south of England, were published in November 2018 in the Lancet. The authors concluded that this approach is likely to achieve “significant impacts” in improving child health and mental wellbeing. Fortunately, we are now achieving and measuring similar outcomes closer to home.

Navigator

For example, this state government’s timely Navigator program has been successful in returning seriously disengaged young people back to a school that they’d drifted away from, to a different school, or to some other vocational and training pathway. As the DET website indicates, Navigator is expanding in 2020.

In the initial pilot, Navigator seems to have run particularly well in Hume-Moreland, where Jesuit Social Services (JSS) have been the (sole) service provider. Their capacity to achieve good outcomes is clearly associated with their experience as facilitators in other programs, including youth justice group conferencing. Some schools involved in the Hume Moreland Navigator project realised that JSS convenors were bringing a particular skill set to facilitated meetings, including the skill of negotiating robust and workable action plans – and that these skills could be highly valuable in schools (i.e. not just in getting young people back into school).

School-wide Positive Behaviour Support Program

The resultant “Engage” program represents the expansion of restorative practices into broader relationship-based educational applications. Reassuringly, but not surprisingly, a yet-to-be-released evaluation of Engage, by Phillips KPA, shows improvements in student and staff wellbeing. During the course of this project, the regional School Wide Positive Behaviour Support coach observed that the skills being imparted to school staff indeed provide some important how to for SWPBS – which might more accurately be understood, even rebranded – as School-Wide Support for Relationship-based Education.

The Education Department oversees the state-wide pool of coaches who help schools implement School Wide Positive Behaviour Support, and the Department is now aware of and interested in this development, i.e. restorative practices, as a practical element in Relationship Based Education, can enhance School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support, Respectful Relationships and related programs.

Supporting this link could align neatly with the overt focus on Relationship Based Education for which Parents Victoria is advocating.

David B. Moore, December 2019

Australian Association for Restorative Justice

Download this article as a PDF ![]()

References

Reimer, K. (2018):

- “The kids do a better job of it than we do”: A Canadian case study of teachers addressing the hypocritical application of restorative justice in their school. The Australian Educational Researcher, 1-15; (2018).

- Relationships of control and relationships of engagement: How educator intentions intersect with student experiences of restorative justice. Journal of Peace Education, 1-29.